The sea has long tugged at the human imagination, inspiring stories of hubristic individuals seeking to tame the inhabitants of that seemingly endless expanse. The ocean has also borne the consequences of excessive modern consumption—commercial fishing, microplastics—paradoxically transforming many of its dwellers into martyrs, pet causes to be championed and protected.

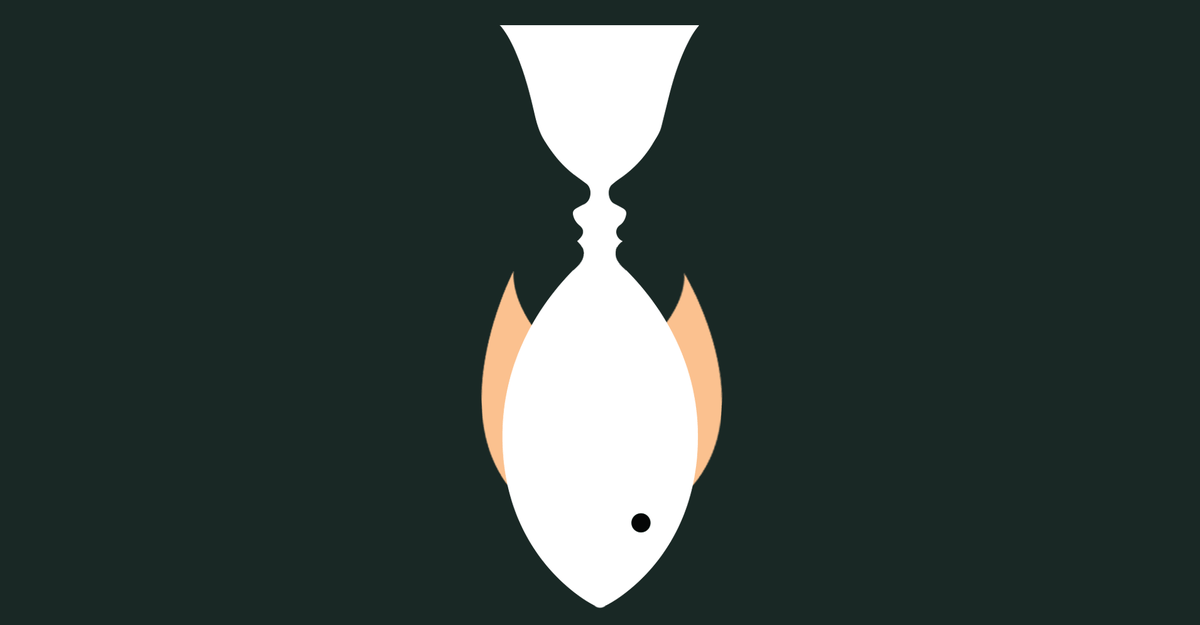

Yet an emergent narrative complicates both these perspectives, positing instead a deep, co-equal bond between humans—particularly those who feel discomfort with rigid taxonomies, or who exist at the margins of society—and sea creatures of the deep. In the new essay collection Voice of the Fish, Lars Horn wonders “how common [it is] to feel completely at odds with being human,” and uses a long-standing fascination with marine life to reimagine the body’s potential. And in the 2020 book Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons From Marine Mammals, the poet and scholar Alexis Pauline Gumbs argues that the lives of marine mammals such as dolphins and whales offer helpful models for resisting exploitation. Aligning herself with these put-upon creatures, she writes, “I am related to all those in captivity.” Though the collections tackle their subjects differently, they would seem to be in conversation with each other, finding in the endurance and fluidity of sea life liberation from human control.

Voice of the Fish attempts to undo ideas of what is “normal” or “natural” by teasing out the expansiveness of marine life. As a child questioning not only their gender but also more existential matters of the body and soul, Horn found comfort in enumerating facts about fish—for example, that some fish species change their sex, or that a particular type of jellyfish can revert to earlier stages of development and reproduce asexually. “Science [has] so often reserved the animalistic for those who fall outside of a society’s dominant ideologies,” Horn notes, alluding to medical experiments on Black men and women, forced sterilization of women with disabilities, and the erasure of transness as a mental disorder. Studying the world of fish, they write, has “helped dissolve a world I found too hard, too strict in how it required me to live within it.”

Finding terms like dysphoria “too clinical, too sterile,” Horn instead seeks to understand their body (an “otherworldly” being) through mystical stories about fish across a variety of disciplines, including ancient myth, the Bible, and the work of classical taxonomists such as Pliny the Elder and Linneaus. In Naturalis historia, for example, Pliny describes sacred eels, adorned with jewelry, that were said to have oracular powers. In 19th-century Japan, watching goldfish in their bowls was thought to cool people down in summer. Tilapia were believed to be protectors of the sun god Ra. Taken by these ethereal tales, Horn wonders, “Maybe this is the nearest we come to the divine?”

Aquariums become, for Horn, both spaces of communion and, paradoxically, reminders of human cruelty. Waiting out a storm at the Georgia Aquarium one day, they find solace in the display of a lone eel. Its presence allows Horn to reflect on the morphological dexterity of the European eel (which changes color and features several times throughout its life) and its general refusal to conform to scientific knowledge. Only moments later, Horn, in turn, is put on display, deemed a “pervert” by a passing family.

The feeling of being exposed, for Horn, dates back to childhood, when their eccentric artist mother had them pose next to dead squids, or in full-body plaster casts. These activities compounded the physical unease Horn felt. But through these and other experiences, they become fascinated by the mutability of their body—as when their ailing foot is mysteriously healed by an animal breeder or when they, for a time, seem to lose the ability to speak, read, or write. Like the fish they admire, Horn observes their body appearing to adhere to a logic more ancient than science alone can explain.

While Horn finds affinity in the strangeness of sea creatures, Gumbs sees them as relatives of a sort, describing her subjects with a startling intimacy. Considering the resilience of family ties, she recounts the story of Tokitae, one of the last survivors of a group of orcas taken from their home in the Salish Sea. Because orcas care for their young communally, Gumbs imagines Tokitae as a mother figure and wonders at her own response: “What does it mean to love someone who has seen her children taken and, at the risk of capture, stayed to witness and scream?" She then directly addresses both the reader and Tokitae: “I love you with a love of screams. I love you with a love of witness.”

Gumbs’s meditations are poetic and inquisitive, often diving beyond anecdotes to tease out what goes unsaid. A heartwarming story of a dolphin mother singing to her child, for example, leads Gumbs to ruminate on the hundreds of women who give birth per year in U.S. prisons. In stories of animal-human interaction, she reads a secret life of marine activism—or perhaps they’re simply acts of survival. As the population of endangered Hawaiian monk seals begins to rebound, including on two islands where U.S. military bases have closed, she optimistically deems their reappearance an act of reclamation. Similarly, when a tropical whale swallows a tour operator (“Not long enough to kill him, just long enough to change his outlook”), she wonders whether it’s an act of protest against human encroachment, rather than a simple accident, as it’s been widely reported to be (“I’m not saying you can’t trust those reports. I’m just saying that they come from the tourist industry, something we also know something about in the Caribbean”).

In the exploitation of these sea dwellers, Gumbs sees an eerie parallel with the transatlantic slave trade, which she argues produced not survivors but “the undrowned,” who breathe “in unbreathable circumstances.” The ability to survive underwater becomes, to Gumbs, a metaphor for human resistance to oppressive institutions, both past and present. The stories of baby seals whose mothers coax them into the ocean before they understand that they can survive in water, mirror, for her, the human potential to meet unexpected challenges. In the “gigantic breathing” of whales, she sees the power of the collective. She cites a 2010 study on whaling and the ocean carbon cycle, which estimated that if whale populations were restored to pre-whaling numbers, they’d be able to store as much carbon as 110,000 hectares of forest. She also uses the blacktip reef shark to push back on the myth of the lone predator that dominates capitalist societies. To Gumbs, their communal nature and sense of play show that “our survival need not make us into monsters.”

At one point, Gumbs addresses both sea creatures and readers with the passion of prayer: “Our kinship is the kind of salve that heals whole oceans.” Horn, too, feels this soulful connection, wondering at the ability of fish to swim “beyond” their body “into some other, mythic, imagined space.” As we continue to face the material consequences of our rising seas, both Horn and Gumbs ultimately turn to a different, more spiritual plane to reimagine the dichotomies between human and animal. In the process, they challenge us to think anew about the way our bodies can, or might be able to, move through the world.

"fish" - Google News

June 27, 2022 at 06:00PM

https://ift.tt/SFv3z9W

The Freedom of Imagining Yourself as a Fish - The Atlantic

"fish" - Google News

https://ift.tt/X5y9Jes

https://ift.tt/f5ByQr8

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Freedom of Imagining Yourself as a Fish - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment